Typo is an outstanding feat by today’s standard; to produce an eight to twelve page, detailed, comprehensive, virtually error free, journal, essentially single-handedly every month; Robert Coupland Harding was a workaholic.

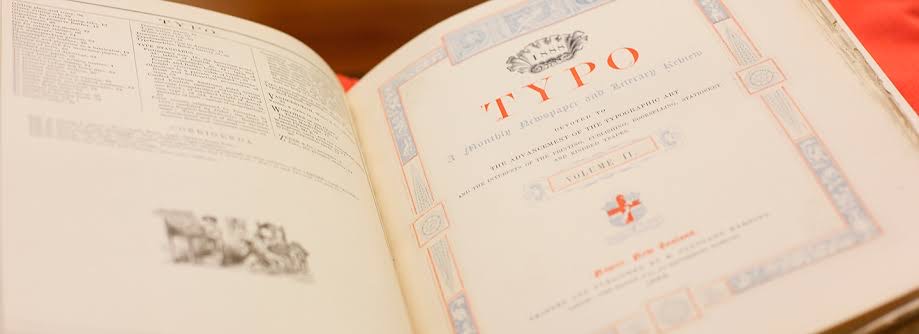

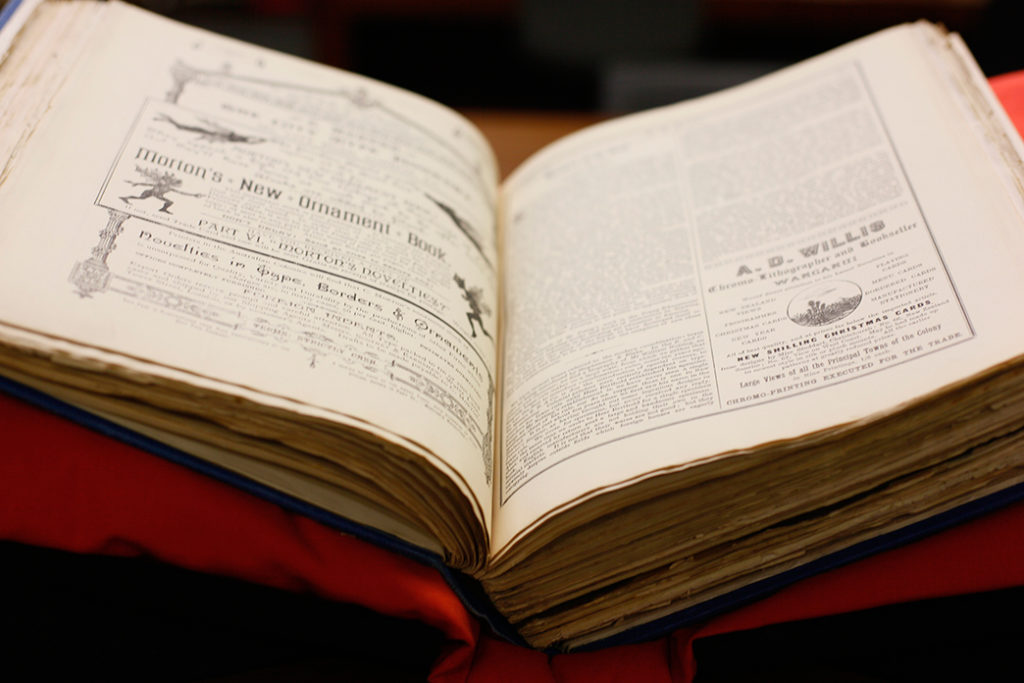

As I stepped into the reading room of the Mitchell Library in New South Wales, my mind brimmed with anticipation. My mission was clear – to delve into the fascinating typographic history of the New South Wales Government Printing Office. Little did I know that this journey of research would lead me to an unexpected treasure – the once-forgotten typographic journal, Typo, by the enigmatic Robert Coupland Harding.

The Mitchell Library, with its vast collection of historical texts and documents, seemed like the perfect place to unearth the secrets of New South Wales’ printing legacy. As I sifted through manuscripts and century-old printing artefacts, I stumbled upon a box that seemed to be nondescript at first glance. But little did I know that within its unassuming confines lay a gem that would electrify my desire for the narrative of typographic history.

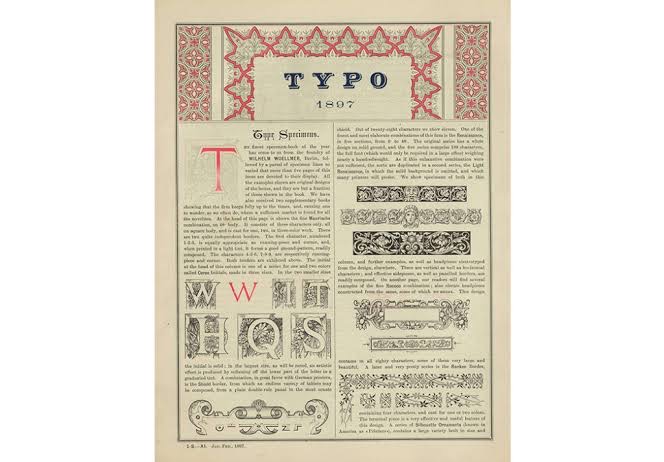

Typo, the brainchild of Robert Coupland Harding, captured my attention from the moment I laid eyes on its pages. This forgotten masterpiece was more than just a typographical journal; it was a testament to Harding’s technical brilliance and artistic vision. Within its covers, I found a world of aesthetics and knowledge, coupled with clear instructions for practical printers – a true treasure of the nineteenth-century typographic world.

Pages of pure brilliance: Within the delicate pages, Harding’s influence on the international typographic community became apparent. His network extended far beyond the shores of New Zealand, reaching countries as distant as France, Germany, America, Japan, and Russia. Typo’s significance as a global communication network was undeniable, bridging the gap between distant lands and erasing the boundaries of the imperial “center” and periphery.

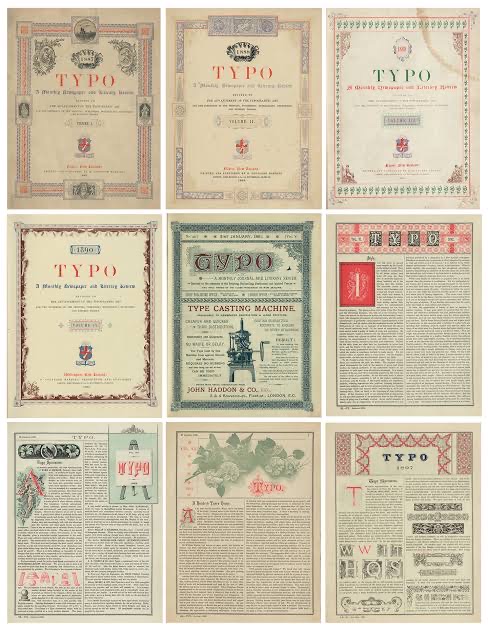

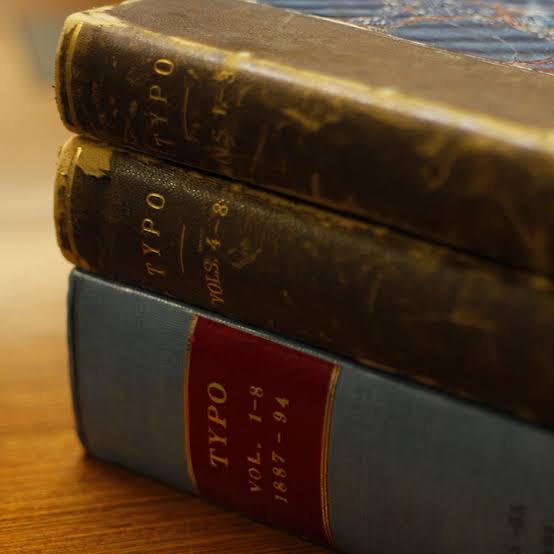

Typo, published monthly as a literacy review and typographic journal between 1887 and 1897 single handedly by Robert Coupland Harding.

As I delved deeper into Harding’s life and legacy, I discovered a man whose passion for printing was only matched by his commitment to social activism and cultural engagement. A man ahead of his time, Harding’s endeavours extended beyond the realm of printing, touching the lives of many through his involvement in various organisations and pursuits.

Typo, published between 1887 and 1897, was an iconic landmark in New Zealand’s printing and publishing history. Although revered in its time, the journal was eventually forgotten, until now. Thanks to a three-year research project funded by the Marsden Fund of the Royal Society of New Zealand, Typo has been rediscovered in its entirety. This digital edition now makes it widely accessible, shedding light on Harding’s unparalleled contributions to the typographic world.

Typo was not just another typographical journal of the 19th century; it stood out for its attention to visual aesthetics. Under the series of articles titled “Design in Typography,” Harding made significant and astute contributions to the global dialogue about aesthetics, offering clear and concise instructions for practical printers. His dedication to the visual display set Typo apart from its peers, making it a truly remarkable publication.

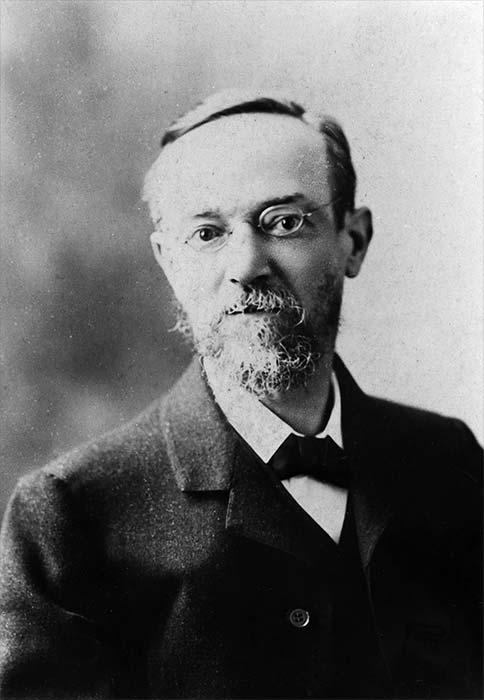

The Life and Legacy of Robert Coupland Harding: Born in Wellington in 1849, Robert Coupland Harding hailed from a family with a rich printing heritage. His father, Thomas Bennick Harding, was a skilled printer and bookbinder who migrated from London to New Zealand. Robert’s journey into the printing world started at a young age, apprenticing with a local printing house. As he honed his skills, he embarked on various ventures, including enlisting in the Napier Rifle Volunteers during the Maori wars and advocating for Maori rights.

Beyond his printing prowess, Harding was actively engaged in social activism and cultural pursuits. He held positions in various organizations, from temperance societies to philosophical societies, and even ventured into politics with the New Zealand Alliance temperance party. Additionally, Harding’s passion for printing extended to creating his own typographic identity, evident in his series of local directories called “Harding’s Almanac.”

The Significance of Typo: Typo marked a turning point in Harding’s career, where his world both narrowed and broadened. While he left mundane printing tasks to others, he established a thriving business that exchanged trade information globally. His network expanded to countries far beyond New Zealand’s borders, making him an influential player on the international market.

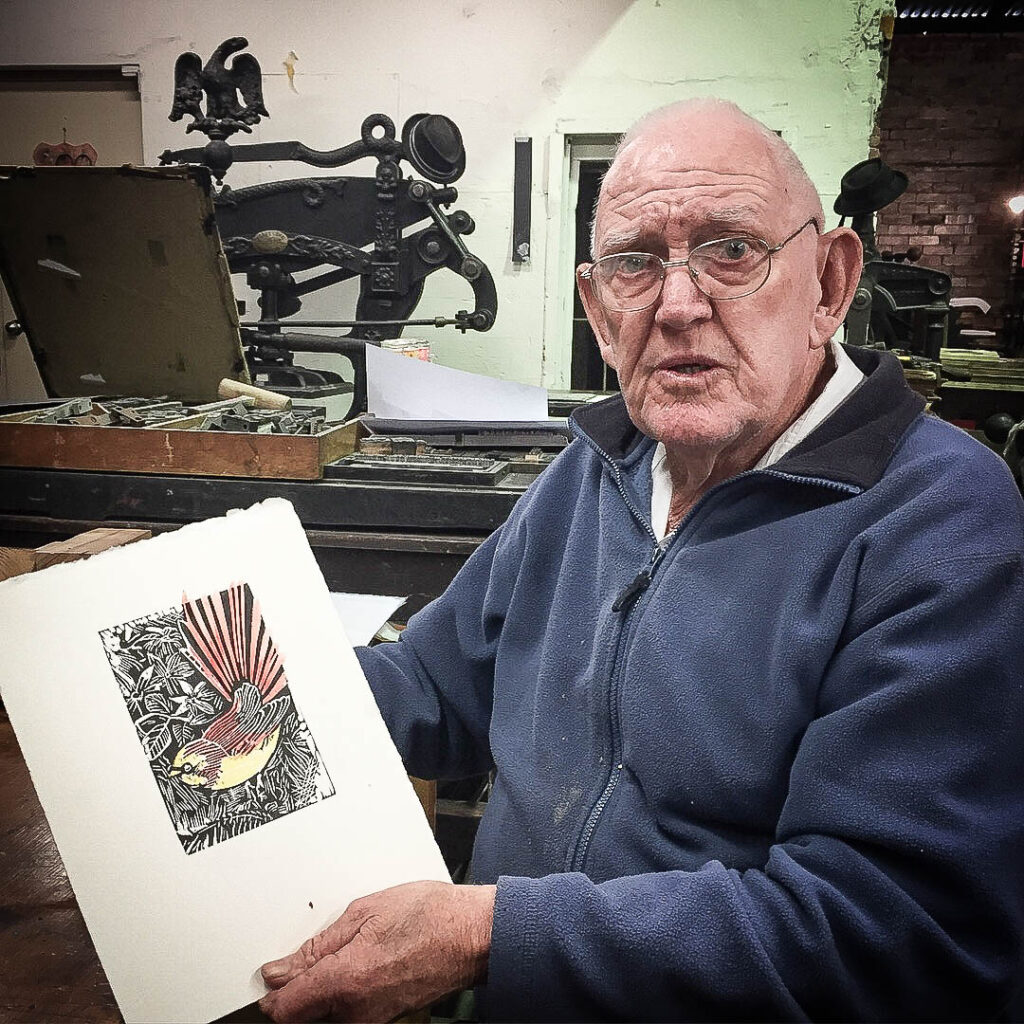

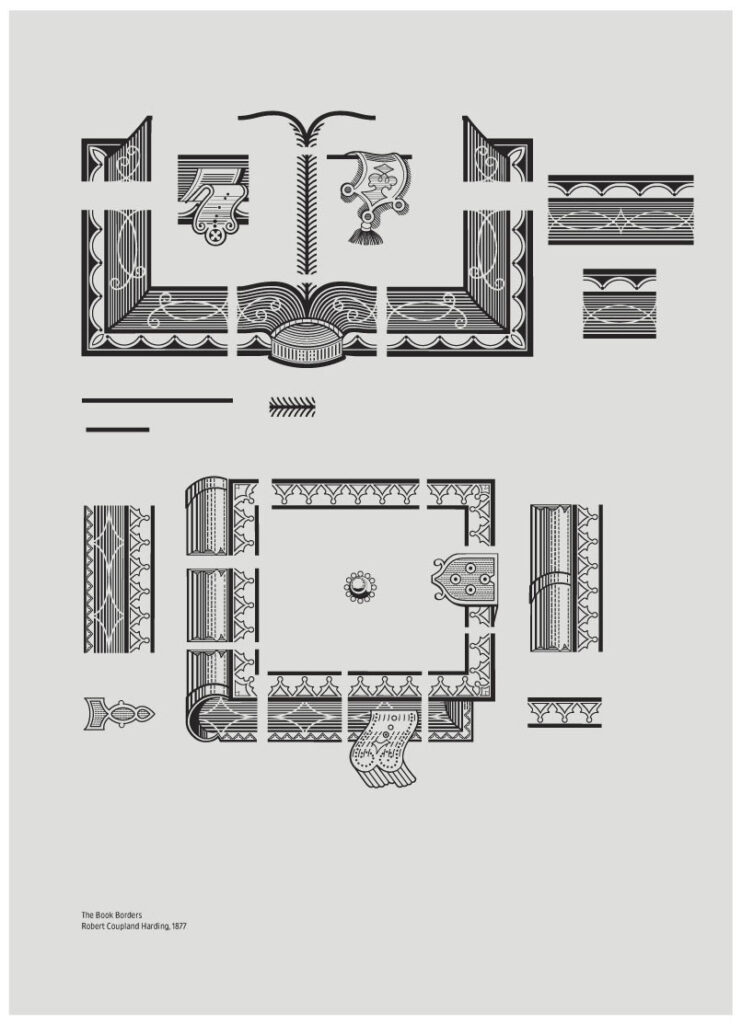

Robert Coupland Harding, The Book Borders, 1877. Digitised by Sai Promsri and Letitia Lam.

The Decline of Typo and Harding’s later life: Despite the accolades and recognition within the printing industry, Typo faced challenges and declined in publication frequency. Harding moved to Wellington in 1890, attempting to revive his business, but the economic downturn thwarted his efforts. Nevertheless, he remained a prominent figure in Wellington, working at the Government Printing Office and contributing to cultural and bibliophilic pursuits.

Coupland Harding died in Wellington on 16 December 1916, survived by his wife, Sophia Sarah Blackmore, whom he had married at Nelson on 15 March 1883, and two daughters and two sons. For all the recognition his achievements received internationally, and his extensive correspondence, he had lived a curiously private life and was something of a melancholic. He was burdened by family anxieties, suffered misfortune in business and had to endure persistent illness. But he was visions ahead of his time, and his aesthetic sensibility and intelligence had a moral dimension which kept him proud in the confidence and independence of his judgement and in his sense of social purpose. It is further testimony to his insight that on the very threshold of the twentieth century he could see printing and typography ‘threatened by the camera, the etching fluid, and by the (at present) harmless and inoffensive “typewriter”, in the keyboard of which lies the germ of something much greater in the future.’

Conclusion: Robert Coupland Harding’s life and work deserve to be celebrated and remembered. Typo, his masterwork, remains an invaluable resource for understanding the nineteenth-century typographical world and its global connections. Through this rediscovery, we can give Robert Coupland Harding the recognition he rightly deserves, positioning him as one of New Zealand’s most accomplished typographers and printers. His impact on the world of visible language and the legacy of Typo will continue to inspire and captivate generations to come.